Every family has stories that get passed down, circulated between siblings and children as noteworthy passages in a family tree.

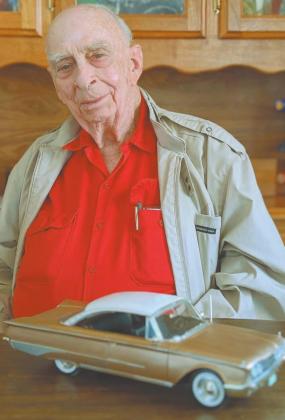

Few are as lively as that of Stephenville resident Bethel Baker, but few family stories center on helping a wrongfully accused man escape a Mexican prison.

“It’s our family story,” said Deb Foster, Bethel’s daughter. “I grew up with this story.”

The story begins with a friendship Baker forged while serving in the Fort Worth Fire Department, one with a fellow firefighter named Carroll Simmons.

“We were firemen and fooled with cars,” Baker said. “[We] considered ourselves somewhat mechanics.”

“I saw where this guy was in prison in Mexico and I didn’t really make the connection immediately because [Carroll and I] didn’t work in the same station,” Baker said. “Somebody said something about [Carroll’s] brother and that’s when I realized it was his brother down there”

“A little later, I got acquainted with his parents,” he continued. “His dad and I were good friends. I was hearing all about D.A. being down there and things that were going on. He was down there 10 years.” “Carroll went on vacation one time. He went down there and came back and said, ‘I’m gonna get D.A. out of there.’ I said ‘how are you gonna do that?’ He said ‘I’m gonna smuggle him out in a car.’”

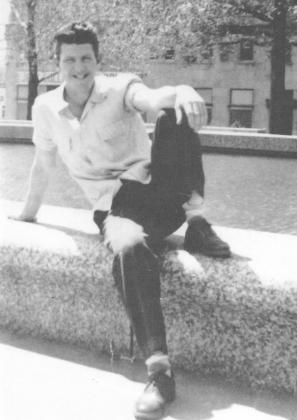

Dykes “D.A.” Simmons

D.A. Simmons was a Fort Worth Crane operator with a checkered past when he started a week-long trip to Mexico on Oct. 14, 1959. He had never been convicted of a violent crime, but he had convictions for burglary and auto theft. He had been treated in two mental institutions, the Wichita Falls Mental Hospital and the Federal Mental Hospital at Springfield.

D.A. drove his brother’s Oldsmobile to the border where the customs official noticed that the vehicle was registered to D.A.’s brother, William Carroll Simmons. The official reportedly advised him to get his tourist card in his brother’s name to avoid complications.

Simmons spent the first night in his car to save money and was shaving in his car mirror when he met Jose Mancha, a resident of Allende who spoke English. In a later interview, Mancha said he found the act ludicrous and started to laugh. They started a conversation and D.A. seemed pleasant enough that Mancha invited him to finish shaving at his home.

D.A. had dinner and visited with Mancha’s family before Mancha drove him to a nearby hotel, where the attendant registered him as “Larry Hall” because he had trouble pronouncing D.A.’s name. The next morning, Mancha was approached by two policemen who had heard that he had been spotted with an American man. They wanted to see him in connection with a triple murder.

A Family Tragedy

About 45 minutes before D.A. crossed the border, Dr. Raul Villagomez was crossing the border to return to Monterrey from a trip to San Antonio. The doctor was traveling with his sisters, Martha (21) and Hilda (18) and his brother, Juan (14).

After passing the federal check point, their vehicle broke down on Route 85. Raul told his family to remain in the car while he hitchhiked to the next big town, Sabinas Hidalgo, for help. Two hours later, he returned to find Juan and Martha dead and Hilda mortally wounded. All had been shot multiple times with a 22-caliber gun.

Hilda was taken to a hospital for treatment for her seven bullet wounds. She told members of “El Norte” newspaper in Monterrey the next day that a blue Chevrolet with Texas license plates stopped in front of their car after Raul left. She reported that a tall blond man with two gold teeth asked if he could offer assistance. He attempted to start the car unsuccessfully.

Hilda told the reporters that they had started laughing at his broken Spanish when he pulled out a pistol and started shooting them.

A Changed Man

This description went into “El Norte” along with a sketch. When Mancha and the police visited D.A., they asked to see his teeth and found that the brunette man did not have any gold teeth or match the description at all.

D.A. had been sought for questioning after a list was made of all persons and cars crossing the border at that time.

Clearing the description, the officers left that morning. That afternoon, Mancha and Simmons were stopped by police who escorted them to the police headquarters in Allende. Mancha was to act as Simmons’ interpreter since D.A. didn’t speak any Spanish.

D.A. reported in later interviews that the authorities beat him and threatened him in order to coerce a confession to the crime.

“El Norte” presented a revised description the next day which described the suspect as having dark, smooth hair and a spot on the upper side of his lip. This matched D.A., who had a scar there. The fact that he used false names on entering the country and at the hotel would also be cited as suspicious behavior.

Simmons was taken to Hilda’s hospital room, where he was presented for a lineup. D.A. was reportedly the only American in the room except for his consulate officer, William Mitchell. D.A. was also noted to be in a white shirt and dark pants while those around him were in scrubs and uniforms.

Mitchell, reportedly not being familiar with Mexican law, didn’t protest to the proceedings.

Hilda was reported to say she was unsure when asked if Simmons was the killer. The prosecutor repeated the question several times after which, the dying witness, said she was ‘almost sure’ that Simmons was the murderer and added, “May God forgive me if I am wrong.”

Hilda died less than two weeks later, on Oct. 29. Meanwhile, Simmons said in interviews, authorities continued trying to coerce a confession with beatings, threats and promised rewards.

Simmons maintained his innocence all the way through his trial. In 1961, he became the first American sentenced to death in Mexico. In 1969, D.A. returned home thanks to his brother, Bethel Baker and some automotive knowhow.

See next week’s Citizen for the rest of the story.

(This article is being written with information provided by the Baker family, pictures and testimony of the Simmons family, archival stories from national publications and a personal account by McHenry Tichenor.)